CRISIS, CATHARSIS, AND CONTEMPLATION

"Art is born and takes hold

wherever there is a timeless and

insatiable longing for the

spiritual."

Andrei Tarkovsky

This “timeless and insatiable longing” has inspired twenty-two challenging, thoughtful and evocative works for display in two extraordinary locations. Their visual poetry opens an unexpected dialogue between contemporary art and the gothic revival Cathedrals of Melbourne and Sydney. For millennia artists have been bridging the invisible with the visible. Similarly, religious tradition has been witness to and reactivated the Divine mysteries which lie at its core. Religious tradition has been witness to the divine mysteries and constantly reactivated their meaning. The gradual forming of a chasm between the contemporary artist and the Church over an interminable period is rarely addressed in contemporary culture. Crisis, Catharsis and Contemplation comes at a time when the Church is in crisis, most contemporary art struggles to engage religion, and our visual contemplation of the sacred is desperately in decline.

Crisis, Catharsis and Contemplation is not an exhibition of religious art. This is an exhibition of contemporary art in a sacred space, which includes the work of religious and non-religious artists alike. The works are not seen as religious where religion is the subject of art, but see art as the spirit or experience of religion. They are inspired by individual experience, influenced by the Christian story, and challenged by their overwhelming location. Sixteen of Australia’s most interesting artists have responded to the space and themes extracted from the liturgy, scriptures and history of Catholics in Australia. Their works engage with the architecture and art in challenging and sometimes confronting ways. Some works are intimately connected with the artist’s own experience of God, others are little more than thoughtful interruptions in the space. All the works stem from a firm belief that the visual arts have been and will continue to be a powerful means of contemplating the sacred.

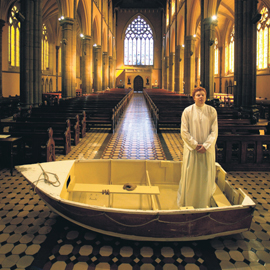

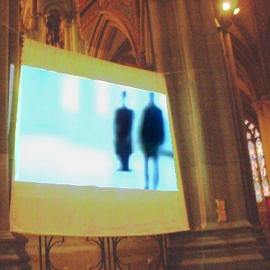

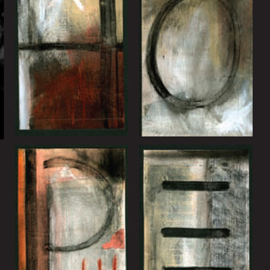

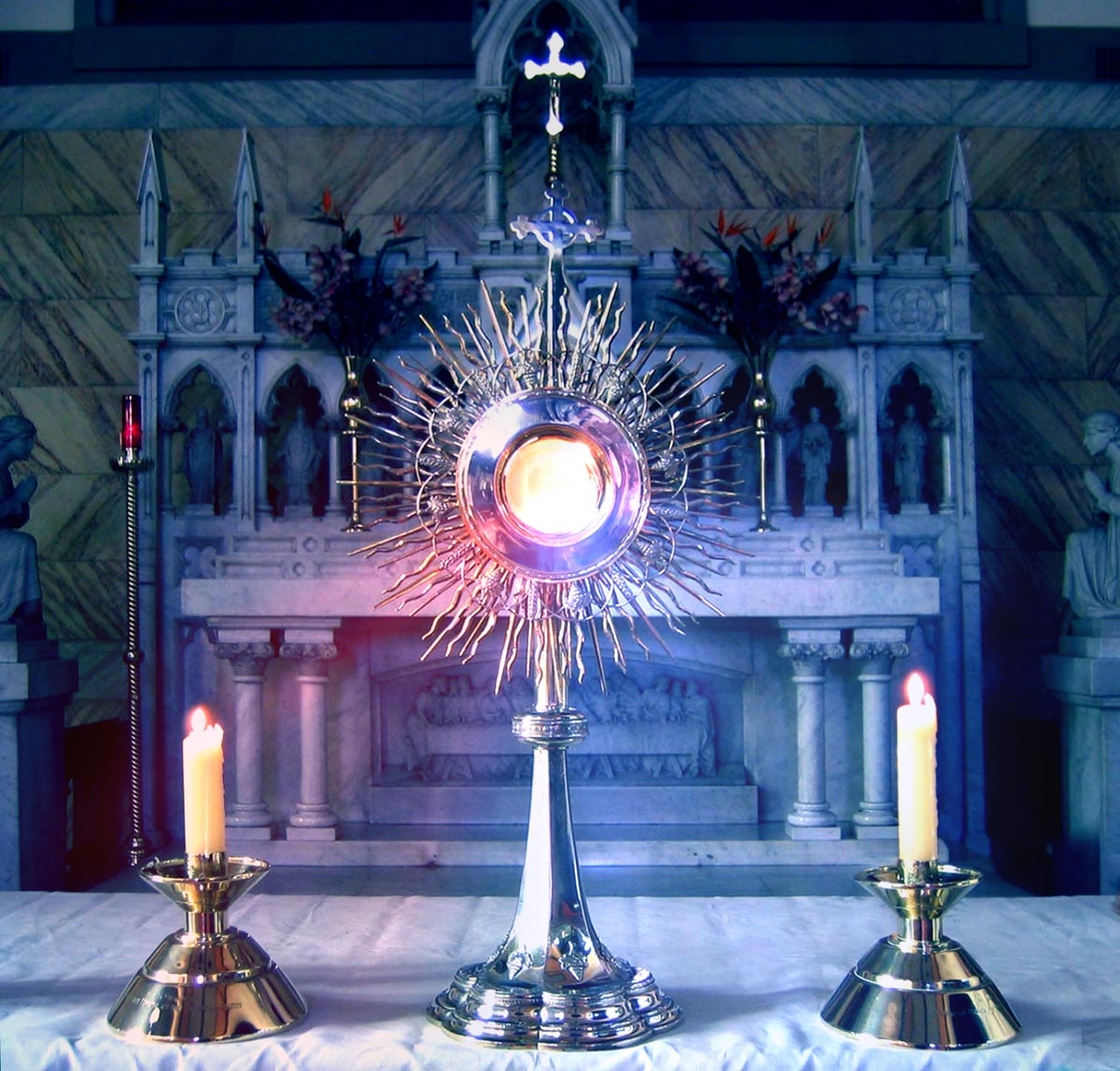

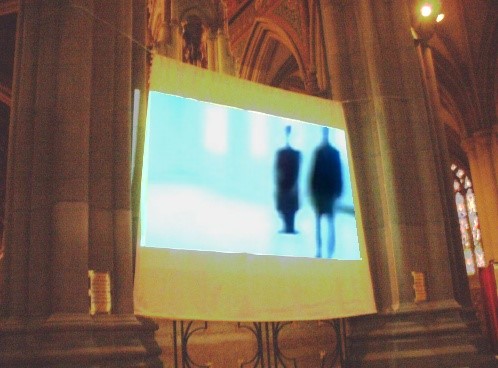

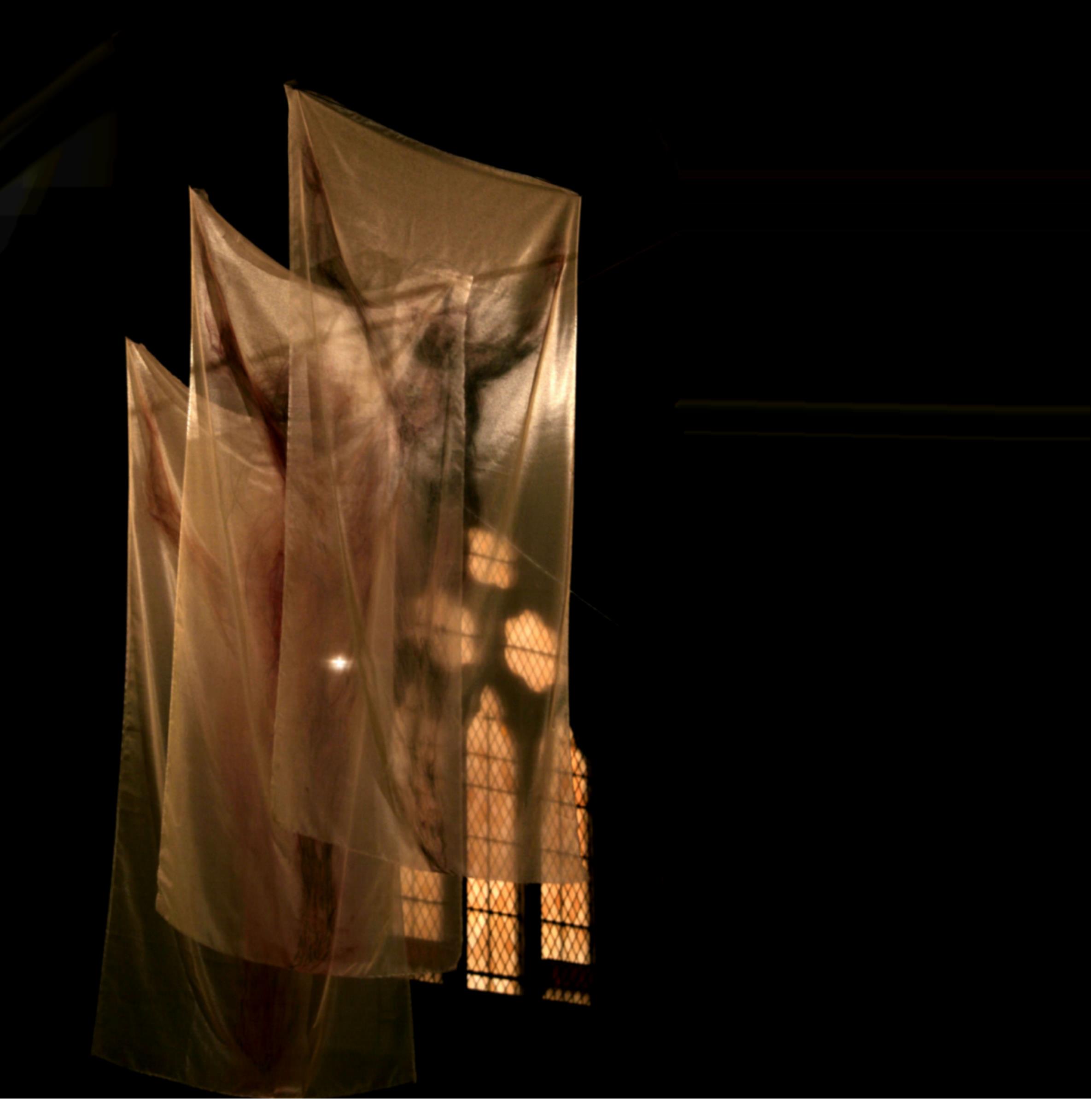

In recent times, through Beyond Belief, World Without End, the Blake and Needham Religious Art prizes, Australian artists have explored religion in their art. Claudia Terstappen exhibited her photographs, film and sculptural installations in Places of Worship at Monash University Gallery last year. Her work begged to be installed in a Cathedral. The location of Fire, Water, Sky & Earth in a shrine challenges us to reflect on television’s potential to take the place of an altar in our lives. On another level, her work elevates the natural elements to a place of reverence. Claudia’s Places of Worship-Japan is made all the more efficacious in the confessional – where an intimate encounter with the sacred takes place. It invites people from other faith backgrounds to explore the similarities and differences in culture, and in particular Sacred space. The investment of devotion, prayer and contemplation in places of worship activates the space and imbues it with an ineffable sense of the sacred. In Australia, there is a similar sense of sublime presence in Churches, Temples, Mosques, Synagogues and Aboriginal Sacred sites – each designated as sacred by the powers that be. James Clayden’s active engagement with sacred space in Ghost Paintings 2 deepens the mysterious character and sacredness of the Cathedral. The distorted figures emerging and disappearing in the haunting atmospheric space are evocative of angels in our midst. Clayton Diack’s short film on the Eucharist also draws our attention toward the divine presence in seemingly finite matter.

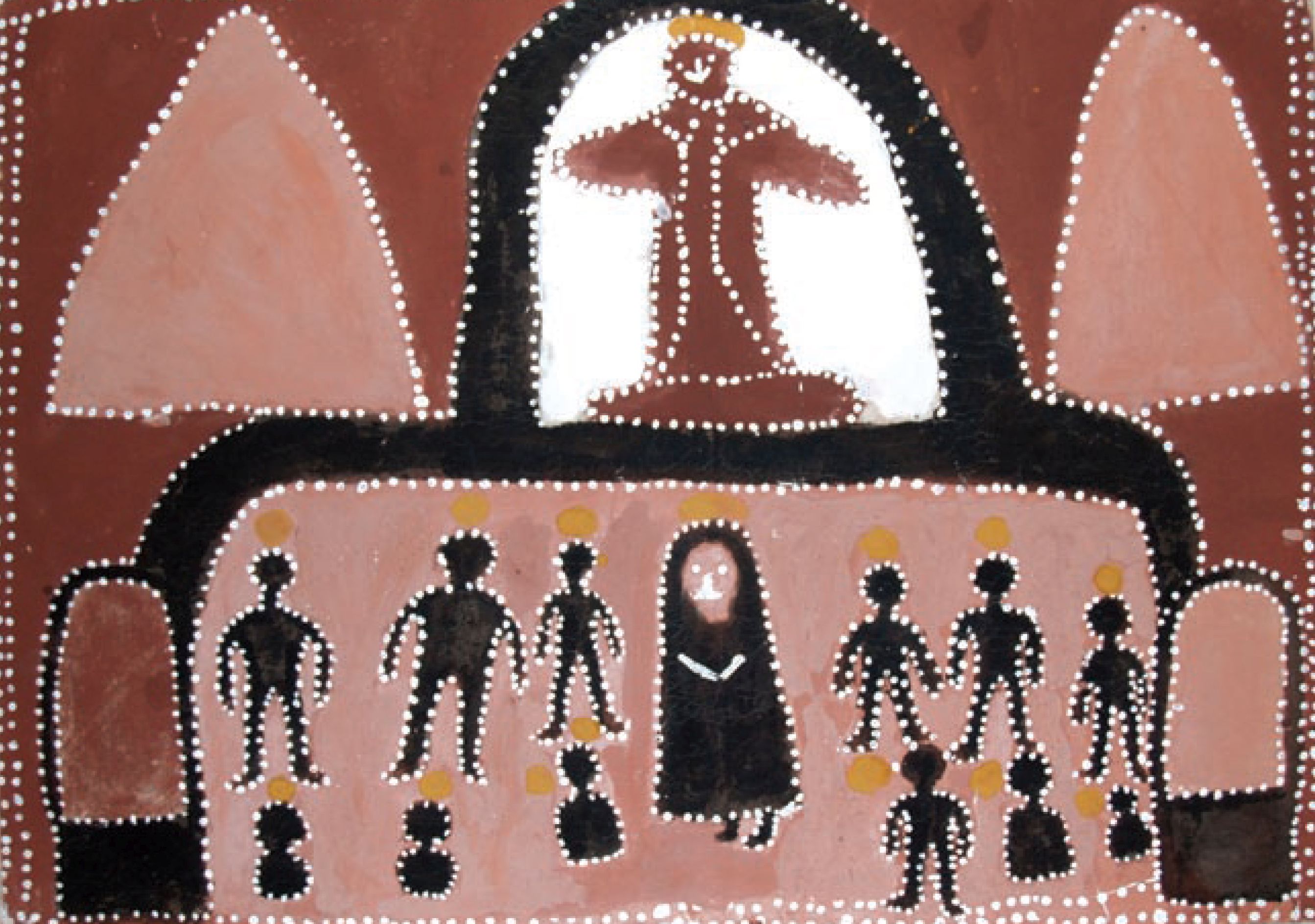

From sacred space to the gift of

storytelling, three works in the

exhibition respond to the history of

Catholics in Australia. Robert

Drummond reflected on the story of

Mary MacKillop, who founded the order

of nuns that taught him in Brisbane.

His vision of Australia’s first

saint-in-waiting’s determination and

resilience grounded in a life of

prayer is an inspiration to all who

struggle for a good cause. Pioneer

looks at the courage and strength of

Australia’s early priests and bishops

who gave their lives in service of a

persecuted and under-resourced Church,

during uncertain times in an

unknowable land.

The poetry of suffering is a theme

that emerged strongly in the works of

several artists included in this

exhibition. The meticulous handling of

paint in Francis Denton’s Pietà

makes for a deeply personal reflection

on grief. He draws on his own

experience of sacrificial love to

create a moving painting of a mother

overcome with sadness. James Waller

and Grant Fraser have opened the

wounds of suffering to reveal a

painful reality frighteningly close to

all. In a glass case and confessional,

the potent words of Waller, Fraser and

Ahkmatova fill the tiny spaces with

trauma and disturbance. In another

glass case, Godwin Bradbeer’s scourged

figure wrapped around a pillar of

paper stands vulnerably exposed.

Beaten and humiliated, Christ wears

his scars for all to see. Patricia

Semmler’s Agony in the Garden, and

Gerhardt Hoffman’s Crucifix chair

point to the hidden scars of mental

affliction. In the Carrying the

Cross, mental illness is seen as

a cross carried by many people in our

society. The hope expressed in Melissa

Hawkless’ works on paper emerges

scratched and carved out of the pages

of Genesis. The creative act and the

work of art can be a healing power in

this troubled world.

The bright light flooding the

south-west corner of St Patrick’s

Cathedral represents the light of

Christ, pouring out from the empty

tomb. Angela Di Fronzo’s Persona

Christi explores the sacrament

of reconciliation and the intimate

space of the confessional as the space

of conversion and healing.

SACRIFICE

The child victim of a landmine

is a symbol of a wound shared by

all humanity and the dismembered

limbs are a painful reminder of

the consequences of war. James

Waller considers the Master

washing the feet of his

disciples a great model of

service and humility. It is an

invitation to serve one another

– to alleviate the suffering and

to share the burdens from our

journey. In acknowledging the

wounded-ness of our brothers and

sisters, we accept that we are

all broken. In the breaking of

the bread, we recognise our own

broken-ness. Clayton Diack’s

film on the Eucharist as the

source of life and rest for the

heavily burdened is ultimately

about a sacrifice. DR

“When power leads us to

arrogance, poetry reminds us

of our limitations. When power

narrows the area of our

concern, poetry reminds us of

the richness and diversity of

our existence. When power

corrupts, poetry cleanses.”

John F. Kennedy

SUFFERING

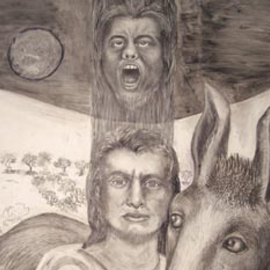

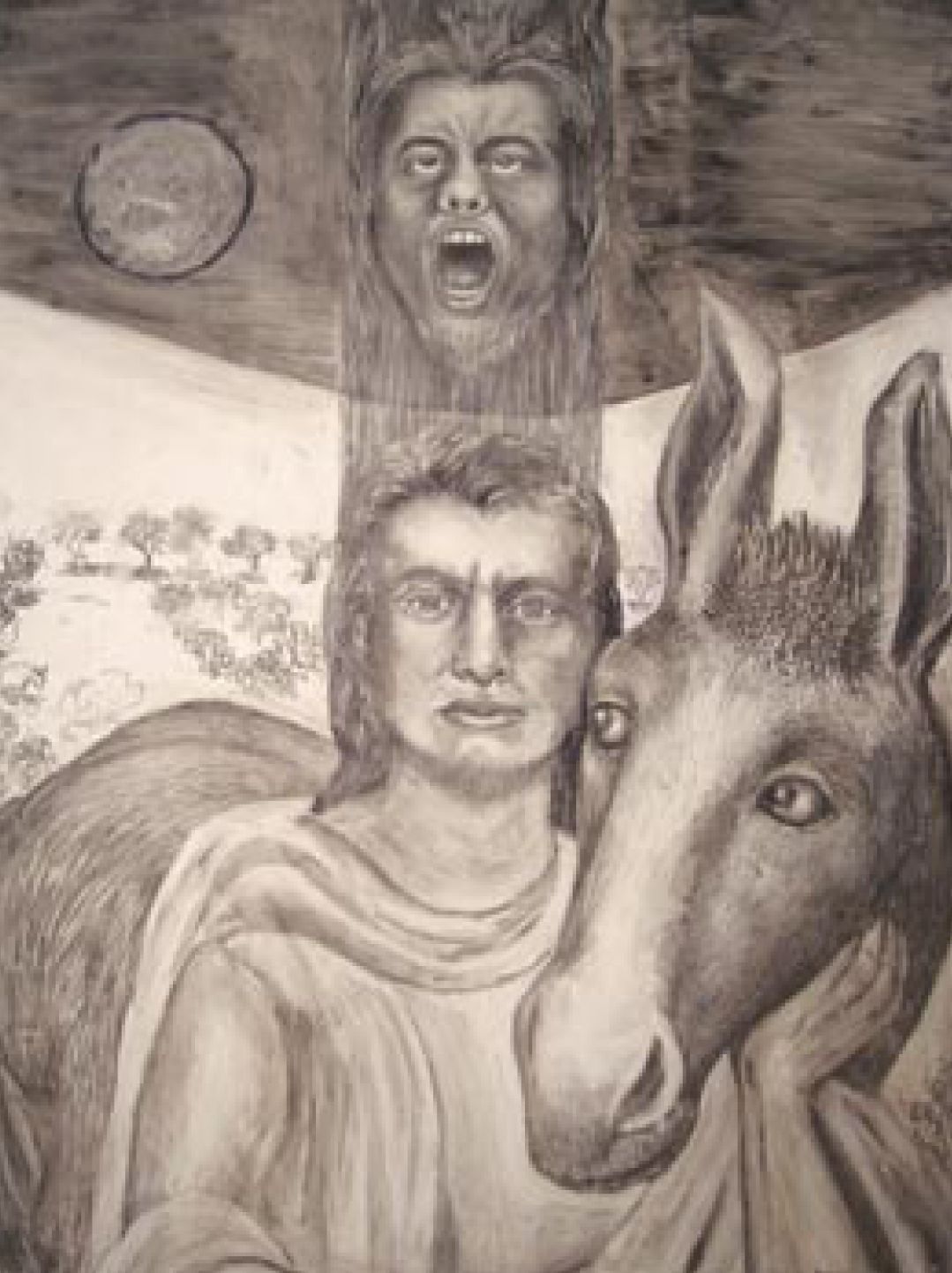

The donkey was present at

the birth of Jesus, fled

with the holy family to

Egypt, carried the Messiah

through Jerusalem and for

Patricia Semmler, could

have been present in the

Garden of Gethsemene. A

symbol of loyalty,

meekness, calm and

companionship, the donkey

comforts Jesus in his

moment of agony. The

absence of anyone but the

scourged figure in

Godwin’s work contributes

to a sense of man’s

vulnerability. The

classically drawn figure

on rolled paper stands

exposed; naked and

scarred. DR

“In a dark time, the eye

begins to see”

Theodore Roethke

MENTAL ILLNESS

One in five

Australians will

suffer from mental

illness at some

point in their

lives.

(www.nhmrc.gov.au)

Gerhardt Hoffman

suffered severe

post-traumatic

stress after seeing

his sister crushed

by a tank in the

Second World War.

The carving marks on

his Crucifix Chair

appear like shovel

grooves as the

crucified artist

tries to dig his way

out of his pain. The

loneliness, mental

torment and

prejudiced

persecution make

mental illness a

very heavy cross.

The Carrying of the

Cross was inspired

by an eccentric ‘top

hat and tails’

character who wears

a larger than life

crucifix around his

neck but carries a

much heavier cross

hidden on the

inside.

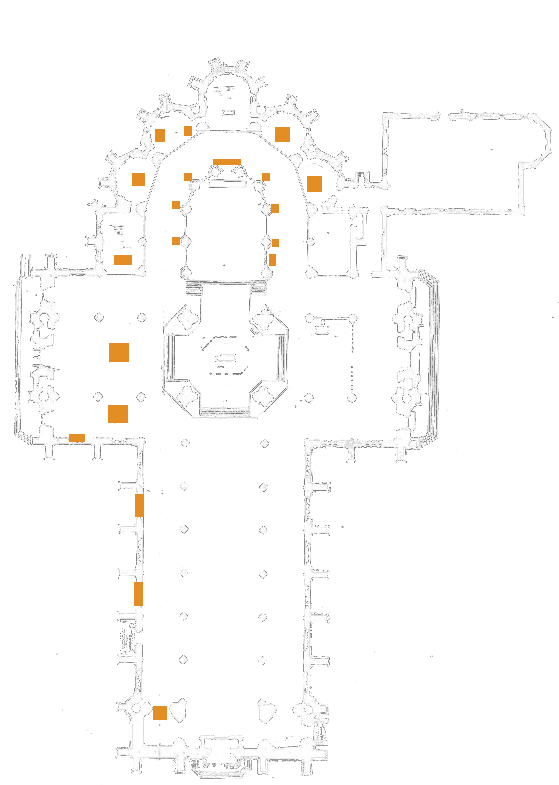

Artworks

Click on area of map to view artwork

INTRODUCTION

It was Pope

Paul VI who

said that the

split between

faith and

culture was

the drama of

our

time. In

another time,

the Church was

the great

patron of the

arts, and

Christian

faith an

extraordinary

source of

artistic

creativity.

But things

have

changed.

The Church

still produces

devotional art

for its own

purposes, and

much of it is

deeply

evocative.

Yet art, for

the most part,

has taken its

leave of the

Church and

Christian

faith, as has

Western

culture more

generally.

The search for

meaning and

beauty tends

to follow

other

paths.

For

Christianity,

the danger

here is that

it can find

itself in a

kind of

billabong in

which it can

only repeat

the forms of

the

past. It

can find

itself a

stranger to

the quest to

forge meaning

and show forth

beauty in ways

attuned to the

deeper

currents of

culture

today.

But this

cannot be the

way of a

Church called

always to

speak the word

of Christ –

ultimately

meaningful,

ultimately

beautiful – in

the idioms of

today.

At the heart

of

Christianity,

there must be

a creative

tension

between the

forms of the

past and the

forms of the

present,

between

devotional art

and art that

stands outside

the circle of

faith, between

sacred space

and the still

resonant

spaces created

by art which,

if not

explicitly

sacred, is

clearly open

to the

transcendent.

Such a tension

will tend to

subvert

conventional

and perhaps

too-easy

perceptions of

meaning and

beauty in

order to bring

to birth new

perceptions

which are more

difficult and

more

revelatory.

That is why

this

exhibition,

Crisis,

Catharsis and

Contemplation,

strikes the

right

note. It

sets the

tension and

strikes up a

conversation

which may at

times be

unsettling but

which can also

be enriching,

even enabling,

both for

Christian

faith and for

art.

Bishop Mark

Coleridge

Auxiliary

Bishop of

Melbourne

ESSAY

"Art is

born and takes

hold wherever

there is a

timeless and

insatiable

longing for

the

spiritual."

Andrei

Tarkovsky

This “timeless

and insatiable

longing” has

inspired

twenty-two

challenging,

thoughtful and

evocative

works for

display in two

extraordinary

locations.

Their visual

poetry opens

an unexpected

dialogue

between

contemporary

art and the

gothic revival

Cathedrals of

Melbourne and

Sydney. For

millennia

artists have

been bridging

the invisible

with the

visible.

Similarly,

religious

tradition has

been witness

to and

reactivated

the Divine

mysteries

which lie at

its core.

Religious

tradition has

been witness

to the divine

mysteries and

constantly

reactivated

their meaning.

The gradual

forming of a

chasm between

the

contemporary

artist and the

Church over an

interminable

period is

rarely

addressed in

contemporary

culture. Crisis,

Catharsis and

Contemplation

comes at a

time when the

Church is in

crisis, most

contemporary

art struggles

to engage

religion, and

our visual

contemplation

of the sacred

is desperately

in decline.

......

Read moreArtist Conversation

The

following is

an edited

transcript of

a discussion

between David

Rastas, Robert

Klein

Boonschate,

Lindy

Patterson, and

James Waller

concerning the

nature of

sacred space

in respect to

the cathedral

exhibition,“

Crisis,

Catharsis, and

Contemplation”.

The discussion

was recorded

in the

artists’

studios, with

works in

progress for

the exhibition

hovering

around and

resonating

with ideas as

they arose.

DR: My hope is

that this

exhibition

will help us

rediscover the

Gothic space.

Contemporary

art in the

Cathedral can

help us to see

with new eyes;

this is not a

game; the

experience is

potentially

transformative.

LP: The space

wishes to have

that

transformative

property.

RKB: Yes, and

it can only

achieve that

through public

interaction.

DR: The viewer

is invited

into the heart

of the space

and it is in

the heart that

this encounter

with the

sacred takes

place.

JW: We are

elevated

through the

space

LP: It is a

consecrated

space; made so

through

ritual.

......

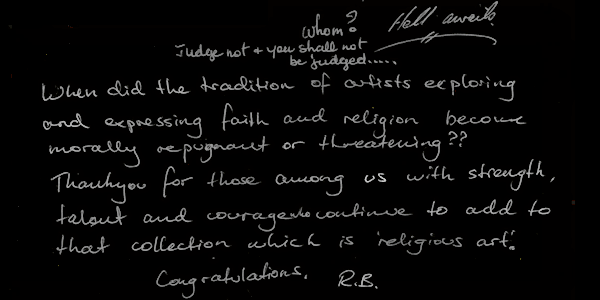

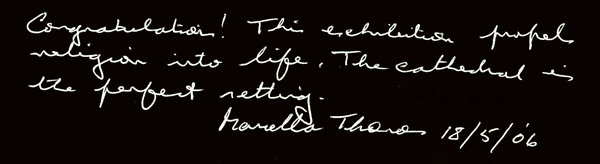

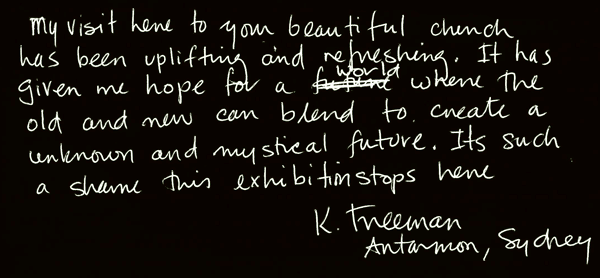

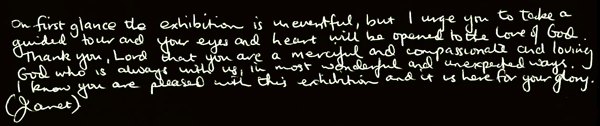

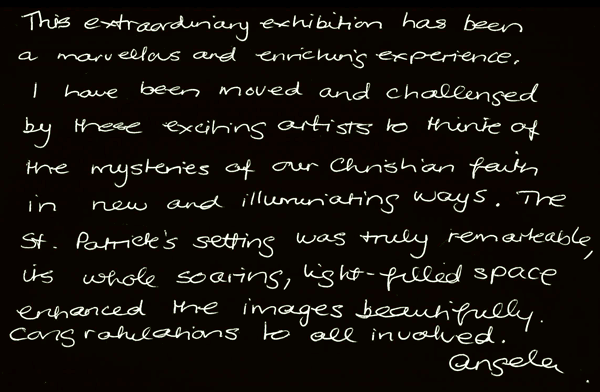

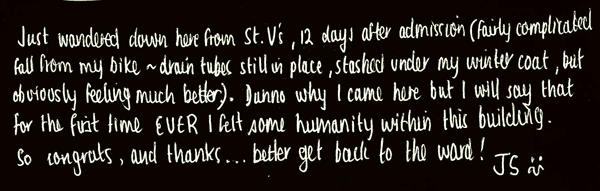

Read moreTestimonials

Crisis,

Catharsis, and

Contemplation

April – May

2006

St Patrick’s

Cathedral,

Melbourne

-

Curator David Rastas

Curatorial Assistants Carly Housiaux and Ishmael Bryce

Catalogue Editor Brendan Rodway

Designer Miriam McWilliam

Contributors Bishop Mark Coleridge and Rosemary Crumlin

Artists Patrick Bernard, Godwin Bradbeer, James Clayden, Francis Denton, Clayton Diack, Robert Drummond, Angela Di Fronzo, Grant Fraser, Melissa Hawkless, Gerhardt Hoffman, Robert Klein Boonschate, Queenie McKenzie, Michael Needham, David Rastas, Patricia Semmler, Claudia Terstappen, James Waller